Article by Nic Fensom

Love.

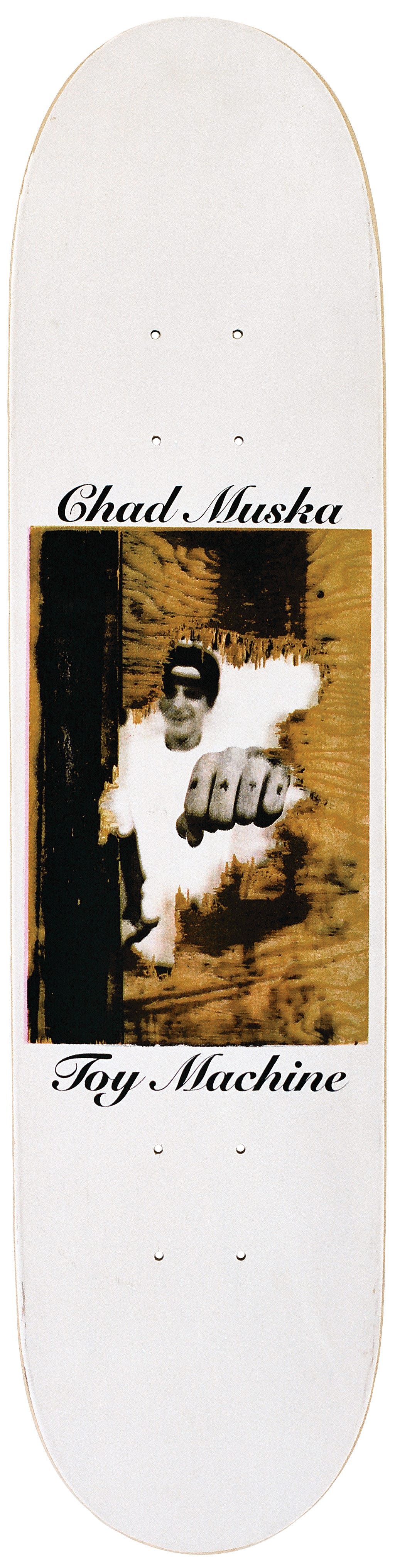

This is one of Chad Muska’s earliest professional skateboards. It hung in skate shops nationwide 16 years before TMZ posted his faded Hollywood graffiti arrest online, nine years before his unlicensed DJ album MuskaBeatz, and eight years before he dated Paris Hilton. The board is titled “Hate.”

“Hate” was made at Tum Yeto, a skateboard distributor slash manufacturer for Toy Machine in San Diego, California, during the summer of 1995. Its graphic was screen printed by a skateboarder with an artist’s eye — someone who cared about skateboarding.

“Those were the lacquer ink days,” said Don Mills, a former screen printer at Tum Yeto. “The graphic had a white background and was, I think, the first four-color process screen print we tried of a photograph. The photo was blurry except for the fist, which was in focus, so it looked OK without being perfectly registered.”

Four-color process is a method that uses four key colors of ink: cyan, magenta, yellow, and black. When cyan, magenta, and yellow are combined at full strength, the resulting secondary colors are red, green, and blue. Registration is the method of aligning overlapping colors on one single image. Since a skateboard is not flat, perfectly placing the surface area of each silk-screen for each color hit of ink is tricky.

“The screens need to stretch a bit to accommodate for the concave, so perfect and consistent registration is not happening,” Mills noted.

On this particular “Hate” print, the magenta ink ran wide by a few millimeters on the left. The silk-screen had stretched a little too much.

In 1989, Mills began printing skateboard graphics for Zorlac up in Miramar before switching to Tum Yeto in 1992. Pros never visited the in-house print shop to inspect his work, except, occasionally, for Ed Templeton, owner of Toy Machine and the artist responsible for creating the brand’s distinctive logos, ads, and board designs.

“Ed would lurk sometimes if there was a special graphic or something with different separations, but he normally sent stuff in,” Mills said. “The pros did not give a fuck or seem to even care.”

The “Hate” graphic was created by Thomas Campbell, another California skater turned gallery-represented artist. Campbell was involved with the defining Beautiful Losers exhibition in 2004. From what Chad Muska remembers, it wasn’t something specifically made to be the graphic.

“Thomas just did it, like, ‘Hey, check this out, what I made,’ Muska recalled, adding, “And then Ed was like, ‘Oh, let’s put that on as the graphic.’”

Campbell had shot the black and white photo of an unknown teenage Muska during a road trip to Las Vegas years earlier. Fist clenched, the word “HATE” is tattooed across Muska’s knuckles. The printed portrait was then placed behind plywood that Campbell had shot with a shotgun, both then combined and photographed once more to become the graphic.

“This idea that this actual art piece was created in order to make that graphic is just insane on its own,” Muska said. “I thought it was an amazing image that represented me.”

Muska’s time at Toy Machine was brief. The drama at the Welcome to Hell premiere at La Paloma theatre in the spring of 1996 shook the skateboarding world. Muska got injured while filming for the video. Stress and expectations erupted that night between Muska, Templeton, and fellow Toy Machine pro Jamie Thomas, who would later be credited for making Welcome to Hell one of the heaviest videos from that era.

When VHS copies of Welcome to Hell arrived at skate shops, Templeton placed a skull over Muska’s face in a group photo on the box sleeve. His name was nowhere to be seen.

Pro for Toy Machine for less than a year, only a handful of graphics intended for Muska got made.

“He was not a strong seller for Toy,” Mills said. “We would do an initial run of 300 or 500, depending on rider and graphic, then a follow-up of 300, again, depending on the rider and how strong the graphic was selling.”

Assuming “Hate” was a single run edition of 300, this specific “Hate” board is a survivor and a testament to the greatness of screen printing — a process that hasn’t existed in skateboard manufacturing for more than twenty years.

In 1999-2000, skater silk-screeners started to get their pink slips. They were being replaced by a large, crude, expensive machine.

Mills said pointedly: “It was the beginning of the Chinese shit.”

“Everything was going to change,” said Gregg Chapman, owner of family-operated Chapman Skateboards, the storied manufacturer and distributor in Deer Park, New York. “Up until that point, the entry barrier to skateboarding was screen printing. Nobody wanted to deal with it.”

Chapman recalls leaving his exhibitor booth at the 2000 Action Sports Retailer trade show in a rental car with fellow mentor and big-wig Paul Schmitt of PS Stix. In a warehouse somewhere near Los Angeles, they had an appointment to view a piece of equipment that had just landed in the States: the first-ever heat transfer machine. With it, a graphic could magically appear on a skateboard in minutes.

“I can’t describe the look on Paul’s face and the way I was feeling when we saw the machine,” Chapman said. “I’m thinking about how this is going to impact all the silk-screen shops.”

Back then, skateboard manufacturers had partnerships with print shops. Printers had their own techniques and tricks. They’d put a lot of energy and time into developing screen-printing methods to look better than the next guy.

“There was so much secrecy about the technique of the curve screens or the swivel screens,” Chapman said.

With heat transfer machines, the dynamics had completely changed.

“It was really like toy technology,” he said, adding, “something from Taiwan was going to come over to California and impact skateboard manufacturing.”

With the push of a button.

Goodbye, sweaty, physical, tedious, hard work. Goodbye gnarly inks, too.

“Whoever had one of these machines had unlocked, in that sense, one of the key rooms; they’ve unlocked one of the big hurdles of producing the skateboards,” Chapman said.

Applying a heat-transfer sheet to a skateboard takes minutes and involves one person to operate the machine. Peel off the plastic protector like a sticker, place the transfer sheet on the board top down and feed it through the machine’s hot iron roller.

An assembly-line operation with so many cycles per hour, if the transfer sheet is flawed, no stress. You don’t bond it to the skateboard. You throw it away.

“When we were direct screen printing, you put all those man hours into a wooden board all the way through to finish,” he continued. “You’d see a lot more boards with slightly imperfect graphics going through, or getting the nod, versus getting kicked out, because when you kick out that bad graphic, you’re throwing away so many man hours.”

With the skateboard industry growing and growing, China was ready to take it.

“You had these big companies like World [Industries], like Girl [Skateboards] that were just marketing companies. They were already competitive and had market share. Now they’re getting even more money for a board, and they have even more momentum,” he said. “That’s where you saw this big shift from the other companies. If we don't do something fast, we’re going to lose more market share to the companies that went offshore.”

It got real cutthroat. Quickly.

“You’d watch the price of the transfer go from being somewhat more in line with direct screen printing to a little bit less to, finally, one person under-cutting the next,” he said. “Next, you’re starting to get phone calls solicited directly from the factory with broken English.”

“Everyone is on Chinese boards and they either don’t care or don’t give a shit because the graphics are cool,” Mills said.

“Nowadays it’s just illustrated — you know, some graphic design kid creating all these graphics in Illustrator,” Muska said.

Skilled designers send Chapman their artwork files. Chapman forwards them on to his connect in China.

“It’s still silk-screening, that’s the other kind of misconception of the heat transfer, and what it is,” Chapman said.

There’s a releasing agent in the heat transfer system that lets go of the heavy, solvent-based inks when heated.

“Instead of you fighting with the 3D of a skateboard and printing on a curved surface, you’re able to print the entire image on something glass-smooth and get really good registration,” he explained.

Tighter registration, higher resolutions, foil options, photo-real images, and heat transfers provide boundless graphic possibilities.

“When we started direct screen printing it was 45 line screens, we thought we were cool, like, ‘Wow, look at that halftone, it looks great,’” he chuckled. “Now fast forward so many years you’re looking at 151, which is pretty intense.”

Further examining this “Hate” print, the halftone dots are easy to spot at 45 line screens. Four layers of lacquer later, you can feel the layers of ink on the board and still see the sheen. After all this time of being exposed to air and temperatures, the graphic has kept its pop.

“You can have silk-screened boards for years and years and years, and you might scratch it and whatnot, but the heat transfer seems to flake off eventually, you know what I mean?” Muska said.

“I do see some of the heat transfer boards expanding and contracting, and they start to get a little crack in them and everything like that, but there are some that don’t,” Chapman said. “There’s so much chemistry going on that I think you’re going to have inconsistent results of which ones are holding up over time or not.”

“Heat transfer boards are just made for quicker turn-around and not meant to be saved, they’re just meant to be skated,” Muska said.

Skated and destroyed. You can’t blame skate companies for using heat transfers.

Now everyone has the sense to hang their boards done by heat transfers as collectibles. Ironically, hardly anyone had the foresight to collect all of the best screen-printed boards from the ’80s and ’90s.

“Hate” was purchased on eBay for $319.97 [in 2012].

After Toy Machine, Muska flipped to Shorty’s. Quickly, he and his signature shadow graphic trended huge for many years, selling strongly through the industry-wide transition.

“Probably at least a five-year span on that graphic, at least, I would say,” Muska said. “I referenced back to the ’80s, when you walked into a shop, you looked up and you knew the graphic that represented the pro that you identified with.”

Chad Muska is still technically pro, only now for his own company.

“People like cycling through new graphics every season just to come up with something new, instead of branding something with the pro, making an iconic image that stands with the pro,” Muska added. “They convinced themselves through sales reps that in order to sell more product, you need to create a new graphic every time.”

And so heat transfer machines stay on (provided they don’t break down), Adobe Illustrator never quits (provided it doesn’t crash) and “Hate” still shines (no matter what).

“When there are boundaries, imperfections, it’s art,” Chapman said warmly. “Every [board print] had somebody’s fingerprint in the ink, the ink was kinda bleeding off this edge, this color didn’t match the last run because the guy mixed it by hand.”

Chapman ended up buying that first-ever heat transfer machine. It still sits on his warehouse floor, in operation, but with little resemblance to its original self due to years of wear, servicing, and makeshift replacement parts.

“We made boards, it’s hard to explain,” he said of the time before heat transfers. “You should have seen what we were doing when we were doing it.”